How artists and musicians make a living today was the subject of much debate this year on my blog and social media accounts and in particular the impact of bootlegging, music piracy and streaming services.

I was accused of being a troll when I called out a so called fan who believed she was being screwed over by a musician and his band when she paid more for tickets to music concerts in Canada than the United States.

I argued that they needed to make a living and concerts were one of the most popular ways in which artists and musicians make money. The demand by fans drives the cost of tickets at particular venues and countries.

This excellent article published in Rolling Stone magazine describes the complicated yet really interesting distribution of music royalties and how some concert ticket prices are at an all time high because they are the preferred way for fans to have an intimate experience with their favourite artists and musicians.

I have copied the article below as I just couldn't explain it in my own words. The article was edited for copyright reasons and no copyright infringement intended.

'How musicians make a living - or don't at all in 2018' by Amy X. Wang published last year in 2018 in the music magazine Rolling Stone on 18 August, 2018.

The buzziest word in music this year is the one that used to be the most utterly boring.

Copyright — ownership of songs and albums as creative works — is a riotous knot of rules and processes in the music industry, with the players much more numerous and entangled than the ordinary fan might think. But between Congress mulling over the much-anticipated Music Modernization Act, plagiarism battles between major songwriters raging and Wall Street scrutinizing Spotify’s lack of profitability as a public company, it’s helpful to have at least a basic understanding of music’s U.S. financial system in order to ponder its future.

To begin with: “Royalties” are the sums paid to rights-holders when their creations are sold, distributed, embedded in other media or monetized in any other way. Here’s Rolling Stone‘s guide to how musicians, songwriters and producers in the digital era actually get their hands on that money.

Recording and Writing Music …

For music listeners, a song is a song is a song. But for the music business, every individual song is split into two separate copyrights: composition (lyrics, melody) and sound recording (literally, the audio recording of the song).

Let’s start with the latter. Sound recording copyrights are owned by recording artists and their record labels. There are further distinctions between different types of sound recording licenses that generate royalties, such as performance rights (for a song’s play on formats such as streaming services, AM/FM radio, satellite radio and Internet radio) and reproduction rights (for sales of physical CDs or digital music files) and sync rights (for song use in film, television and other media) — but for the most part, what matters is that this copyright only belongs to artists and whatever label is behind them.

Those parties may have nothing to do with the people who write the lyrics and melody of the song and thus own the composition copyright. Sometimes they’re one and the same, in which case that lucky party gets double the cash flow. If they’re separate — as is the case with most pop songs and chart-topping hits — the sound recording copyright is split between artists and record labels, while the composition copyright is split between whatever songwriters and publishers are involved. In the case of Counting Crows’ “Big Yellow Taxi,” for example, the band takes sound recording royalties but Joni Mitchell, the song’s original writer, gets composition royalties.

For the majority of times when somebody listens to a song, both types of copyright kick in, generating two sets of royalties that are paid to the respective parties...

… and Getting That Music Played

Let’s break that down by the most popular ways listeners actually contribute money to music’s creators: When someone buys a song from iTunes, Google Play or any other digital store, money from that sale is paid out to creators via both copyrights — composition and sound recording — with the rates depending on label size, distributor size and specific negotiations between the two as well as any other middle parties involved. (Sometimes labels work with agents that can license bigger catalogs all at once, saving time and trouble but wedging in an extra fee.)

The same dual-copyright payout essentially happens in the case of on-demand streaming, as well as when a song is played in businesses and retailers whether that’s grocery stores, hospitals or in the background of a startup’s website. The specific percentage payouts within these deals depends on the type of service and the negotiating power of all the names involved.

Putting music in film and television and commercials, a.k.a. “synchronization,” involves a license negotiated between content producers and publishers/songwriters. A fee is paid upfront, and royalties are also paid once the particular film or television show has been distributed and broadcast. Sync licenses can be lucrative and, because most filmmakers generally choose music based on their own whims rather than what’s at the top of the charts, also serve as a decent discovery platform for under-the-radar acts.

The process is further different for radio services, though, which typically use blanket, buffet-style licenses that determine payment rates on mass scale. And there’s an important distinction made in current copyright rules between broadcast radio (AM/FM) and Internet radio (Pandora, SiriusXM, other satellite radio and webcasters): Terrestrial radio broadcasters don’t have to pay sound recording copyright owners, while the second group does. That difference — which the music industry largely considers an unfair loophole — means that whenever a song is played over the airwaves, it only makes money for its writers, not artists. So whenever Counting Crows’ “Big Yellow Taxi” is played over AM or FM radio, only Joni Mitchell gets paid and the band gets nothing.

Performing Music Live

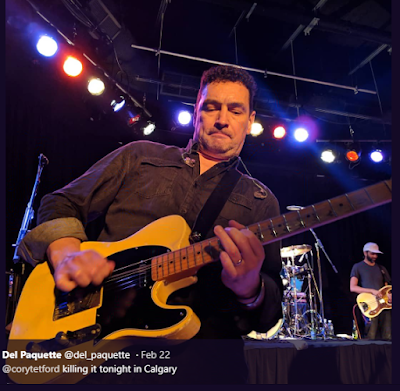

Live events are quickly shaping up to be the most lucrative space for musicians in the digital-music era, and for good reason: As listeners become inundated with cheap access to music provided by streaming services, dedicated music fans crave more intimate experiences with their favorite artists. That’s why tours are getting grander and music festivals are drawing ridiculous crowds even if their lineups are all the same. It’s also why concert and ticket companies like Live Nation are growing like crazy.

While album sales dwindle and streams may only pay out fractions of a cent at a time, live shows — be it tours, festivals or one-off concerts — are commanding some of the highest ticket prices ever.

Advertising

In the heyday of pop and rock, musicians rarely wanted to be associated with corporate brands, but that’s changing with the rise of rap as America’s most popular genre. Brand partnerships offer artists the ability to sponsor or endorse a brand they might genuinely like, and get access to an additional revenue stream while they’re at it. Another way musicians find side money is from YouTube monetization, wherein YouTube videos share in the profit from the ads that come tagged onto them. Psy’s “Gangnam Style” reportedly made $2 million from 2 billion YouTube views. YouTube’s head of music Lyor Cohen wrote in a blog post last year that YouTube’s payout rate in the U.S. is as high as $3 per 1000 streams.

Fashion, Merchandising, and Other Direct Sells

Selling non-music products like perfumes, paraphernalia and clothing lines is an easy money-making strategy that artists have been taking advantage of for decades — but in the digital era, musicians can also get creative with their methods, expanding well beyond traditional merch tents at concerts and posters on a website.

Artists are also starting to ask for money from audiences directly — via crowdfunding or creating custom channels of communication with their fans — outside of social media platforms like Instagram and Twitter. The Voice star Angie Johnson raised roughly $36,000 on Kickstarter to record an upcoming album, for instance. More groups are releasing dedicated apps or subscription packages for their music or selling bespoke products like artist-curated festivals, email subscriptions and limited music releases. Pitbull has his own cruise.

So Then — Where’s All the Money?

All of the above is by no means a comprehensive list of ways that modern artists make money; keep in mind that it’s also now easier than ever to switch lanes and become a producer or writer for someone else’s music, as is the case with Bebe Rexha’s journey from songwriting to recording or American R&B hitmakers’ move to South Korea’s K-pop industry (which complicates the royalties splits a bit by involving copyright law from overseas, but nonetheless brings back significant money). The sheer number of different revenue streams available to musicians is higher than it’s ever been in the past.

And yet, the average modern artist is still strapped for cash.

By recent research estimates, U.S. musicians only take home one-tenth of national industry revenues. One reason for such a meager percentage is that streaming services — while reinvigorating the music industry at large — aren’t lucrative for artists unless they’re chart-topping names like Drake or Cardi B. According to one Spotify company filing, average per-stream payouts from the company are between $0.006 and $0.0084; numbers from Apple Music, YouTube Music, Deezer and other streaming services are comparable. That creates a winner-takes-all situation in which big artists nab millions and small ones can’t earn a living wage. It’s nothing new — one could argue that such were the dynamics in almost every era of music past — but the numbers are more dramatic than before.

Another reason: the sheer number of brokers, middlemen and other players in the music industry, as detailed above. And that’s not to mention the black box of royalties in the streaming era, a pit of unpaid money that hasn’t yet made its way to artists because of faulty metadata or bad communication amongst the various services involved in reporting the proper numbers; its worth has been estimated in the billions. “When you end up tracing all the dollars, around 10 percent of it gets captured by the artist. “That’s amazingly low,” Citigroup’s media, cable and satellite researcher Jason Bazinet tells Rolling Stone. “These young artists — you don’t even understand the gory details of the music industry or how the dollars flow. You’re really not going to make that much money. There’s an unbelievable amount of leakage through the whole business.”

Good news: The music industry has now accepted streaming as its revenue-leader and is poised to adapt around that, with many analysts and experts expecting that the business will streamline itself — with rewrites of law, new royalties negotiations, mergers, acquisitions and consolidations — into something leaner and, finally, more lucrative for musicians. Bad news: No one knows when that will be.